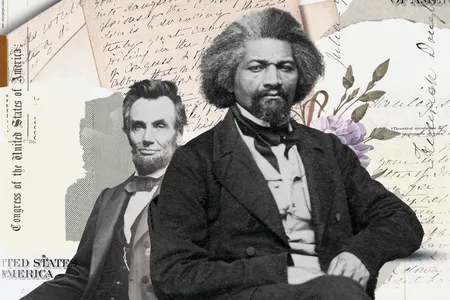

In correspondence with a passionate abolitionist in London, the great American orator didn’t hold back when talking about the 16th president, or his successor, the much-maligned Andrew Johnson

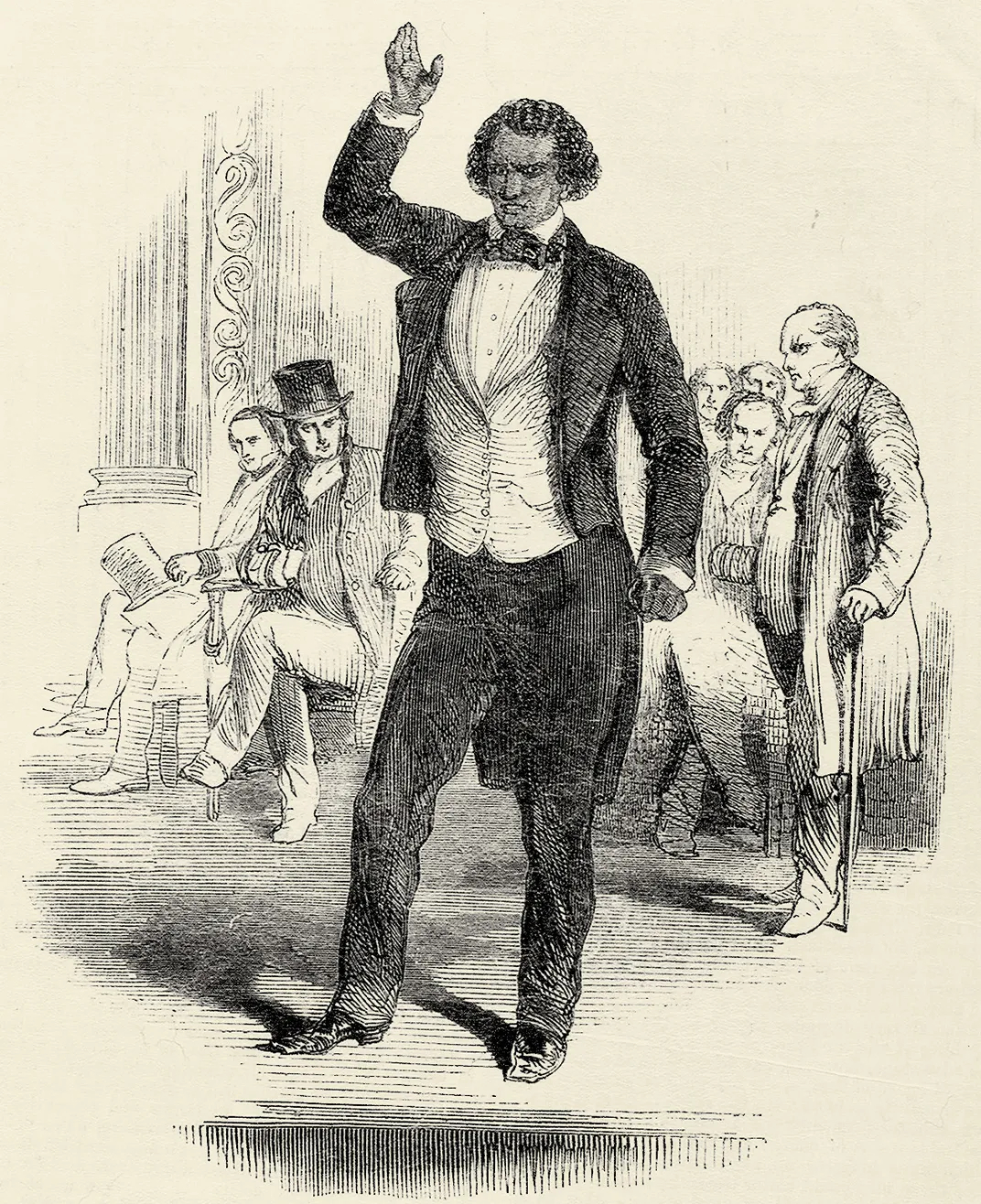

A visit to Newcastle, England, in 1846 led to one of the most consequential friendships in the history of abolitionism. There, historians believe, Frederick Douglass, 28, met Julia Griffiths, a 35-year-old activist, who showed him around London. Griffiths (later known as Julia Griffiths Crofts upon marriage) would recall Douglass’ playful ease with her and her younger sister, Eliza, at a soirée in London the following March. After Eliza pinned a white carnation on Douglass’ coat, “naughty brother Frederick never rested til he knocked off the beautiful white petals, leaving only the green leaves.” Griffiths gained Douglass’ confidence by raising funds for his abolitionist work, and the pair developed a deep bond, becoming co-laborers in the cause of Black freedom and equality in the United States. Their 47-year-long correspondence, much of it resting among Douglass’ papers in the Library of Congress, has become a critical piece in historians’ portraits of Douglass.

Those papers, though, are incomplete, and scholars have long wished to fill in what’s missing. Now, we’ve found that a number of significant letters from Douglass have been hiding in plain sight, including some remarkable ones he sent to Griffiths during the Civil War. At pivotal moments, Douglass shared candid opinions with Griffiths that he never conveyed to American audiences, revealing surprising views on Andrew Johnson and Abraham Lincoln.

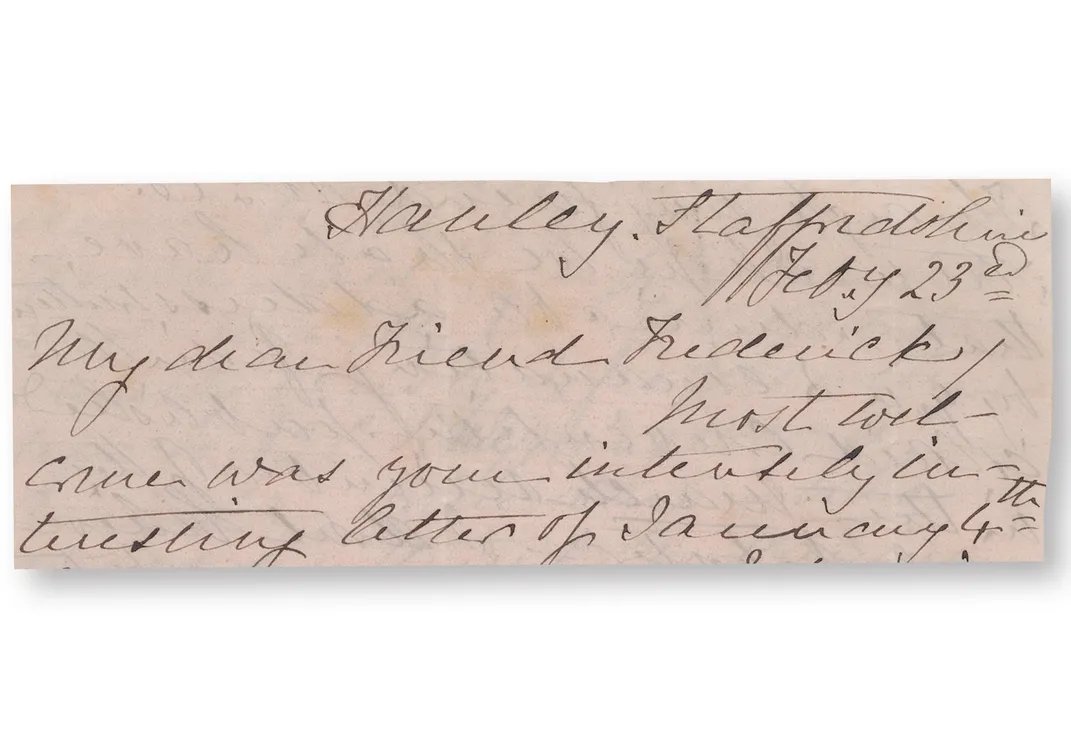

In a February 1865 letter to Douglass, Griffiths prays that God may “watch over you and permit you to see all your people free!!” Library of Congress

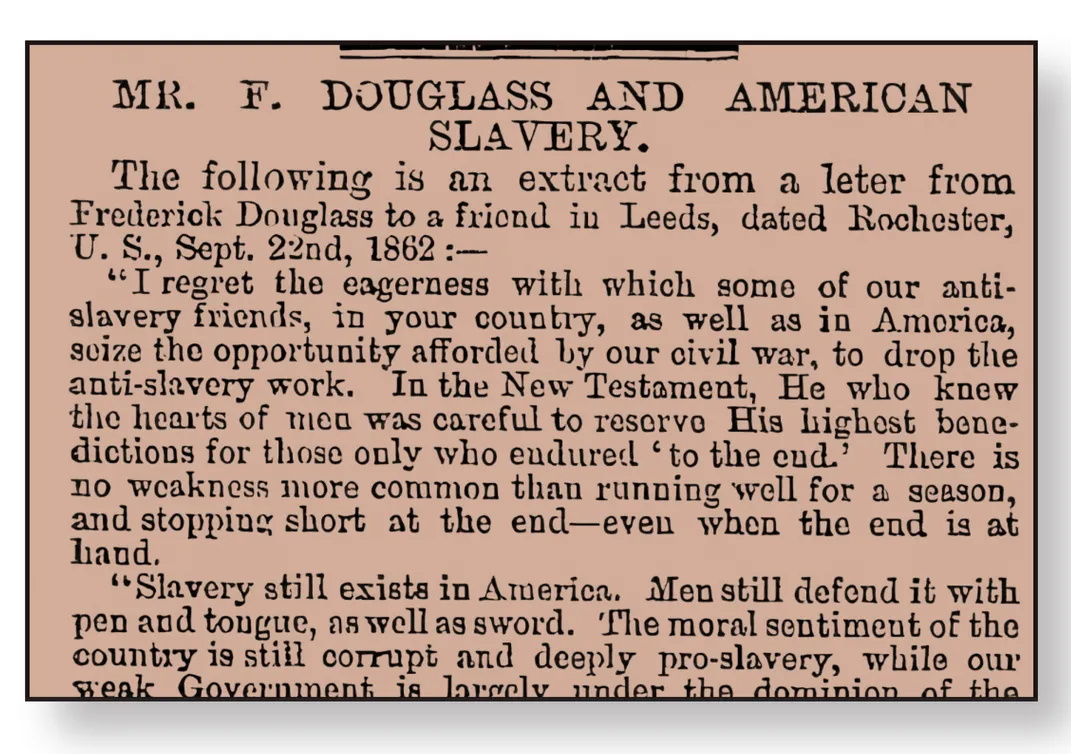

Following a common practice in 19th-century publishing, especially for news from abroad, Douglass printed more than 80 of Griffiths’ letters between 1855 and 1863 in his newspaper. In turn, Griffiths often gave Douglass’ letters to the Leeds Mercury to publish. With this knowledge, we scoured online databases and found eight remarkable letters Douglass sent to Griffiths and other English abolitionists.

These have never been anthologized or even quoted by modern scholars; we reproduce them for the first time in our new volume, Measuring the Man: The Writings of Frederick Douglass on Abraham Lincoln. Leigh Fought, a historian at Le Moyne College and author of Women in the World of Frederick Douglass, calls it “thrilling,” in these letters, “to watch Douglass in real time as he critiques and reacts to Lincoln, vacillating between optimism and despair in dizzy frustration.”

In 1849, Griffiths moved from England to Rochester, New York, to help on Douglass’ newspaper, the North Star, where the woman whom Douglass called “my industrious and vigilant friend and co-worker” became his office manager, copy editor and chief fundraiser. By day they worked together in the offices of the North Star; at night Griffiths lived in Douglass’ home with his wife and five children. Rumors circulated that Douglass and Griffiths were having an affair. In late 1852, she left the house—by some accounts, at the insistence of Douglass’ wife, Anna.

An engraving of Douglass addressing an English audience during his visit to London in 1846—likely the same trip when he forged a fateful acquaintance with Griffiths. Library of Congress

Griffiths returned to England in 1855 and four years later married Henry O. Crofts, a Methodist minister. Douglass rarely returned to England, but the two remained close friends. In 1862, she wrote, “I wish I could fly over the water and have a consultation with you.” She continued to help fund his work.

At the outset of the war in April 1861, Douglass publicly called for Lincoln to free the enslaved and allow Black men to fight in the Union Army. The president rebuffed such calls, concerned that emancipation lacked a clear military justification and would provoke the loyal border slave states, such as Maryland and Kentucky, into joining the Confederacy. A year and a half later, on September 22, 1862, with the border states firmly within Union control but the rebellion ongoing, Lincoln issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, threatening to free enslaved people on New Year’s Day if the rebel states did not return to the Union.

In a letter to Griffiths written on November 11, 1862, Douglass observed that a swift Union victory would have left slavery untouched. He also noted the irony that emancipation was finally coming about because a slow-moving, anti-abolitionist general, George B. McClellan, had been kept in command of the Union Army for so long: “Had his place been filled by an earnest man, with the means at his command, the rebellion might have been crushed in its infancy, and slavery might have lived to entail horrors on the slave and to insult Heaven yet a long time.”

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln declared that “all persons held as slaves” in rebel-controlled territory “are, and henceforward shall be free.” The Emancipation Proclamation also allowed Black men to join the Union Army. Douglass lamented that the proclamation was issued for military reasons rather than as a “grand moral necessity” but was gratified that Black men could enlist. Over the next two years, almost 200,000 Black men fought for the Union. Douglass played a major role in recruiting Black soldiers and proudly watched two of his sons go off to war.

After Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, Douglass expressed “deep grief” to his neighbors in Rochester, and he urged that the crimes of the Confederacy not be forgotten. “Let us not be in too much haste in the work of restoration,” he warned.

An 1862 letter from Douglass, printed in the Leeds Mercury, exhorts abolitionists not to “drop the anti-slavery work” even amid the Civil War. Library of Congress

Douglass’ concern led him to make a startling confession to Griffiths. Five days after Lincoln’s death, he wrote: “Mr. [Andrew] Johnson is, in many respects, better qualified for the work to come than was Mr. Lincoln.” Given the evidence, Douglass’ expectation was not unreasonable. As military governor of Tennessee during the Civil War, Johnson had gained a reputation as a Southern Unionist who supported freedom for the enslaved. In October 1864, he emancipated those enslaved in Tennessee (a state exempted by the Emancipation Proclamation because it was under Union control) and told a gathering of Black Tennesseans, “I will indeed be your Moses.” Johnson spoke of a future where all “loyal men, whether white or black” would have “a fair chance in the race of life.” Within days of becoming president in April 1865, he declared of the defeated Confederates: “They must not only be punished, but their social power must be destroyed.”

Douglass believed the new president would punish former Confederates in a way that Lincoln would not have. In a letter to Griffiths on April 20, 1865, he wrote that, “when confronted by apparent repentance” of former Confederates, Lincoln’s “wonderful moderation, his remarkable caution and his extreme amiability” would have softened him, sparing disloyal white Southerners “the loyal wrath their crimes have provoked.” Douglass said Lincoln would have given ex-Confederates back their land and restored their citizenship rights, requiring only the abolition of slavery—not full enfranchisement for Black men. Johnson, by contrast, had lived in slave states his entire life, and so “better understands than Mr. Lincoln did the necessity of putting down not only slavery but the slave power.”

This story conflicts with the hopes Douglass had conveyed to Griffiths in April 1865. He never voiced his enthusiasm for Johnson to any American while they mourned their martyred president. By the time Douglass memorialized Lincoln as “a progressive man” in a speech honoring Lincoln’s birthday in 1866, he drew a pointed contrast with Johnson. Lincoln, he said, “did not begin as a Moses and end as a Pharaoh.”